Have you ever noticed new dark spots appearing on your skin as the years pass? Perhaps you've counted more moles on your arms, back, or face than you remember having in your younger years. This common observation raises an important question: Why We Get More Moles As We Age: Sun Damage, Hormones, and Genetics Explained is a topic that concerns many people as they notice changes in their skin over time. Understanding the science behind mole development can help distinguish between normal aging processes and warning signs that require medical attention.

Moles, medically known as nevi, are clusters of pigmented cells called melanocytes that appear as brown, black, or tan spots on the skin. While most people develop their first moles during childhood and adolescence, the journey doesn't stop there. The relationship between aging and mole development involves a complex interplay of sun exposure accumulated over decades, hormonal fluctuations throughout life stages, and genetic predispositions inherited from parents. 🔬

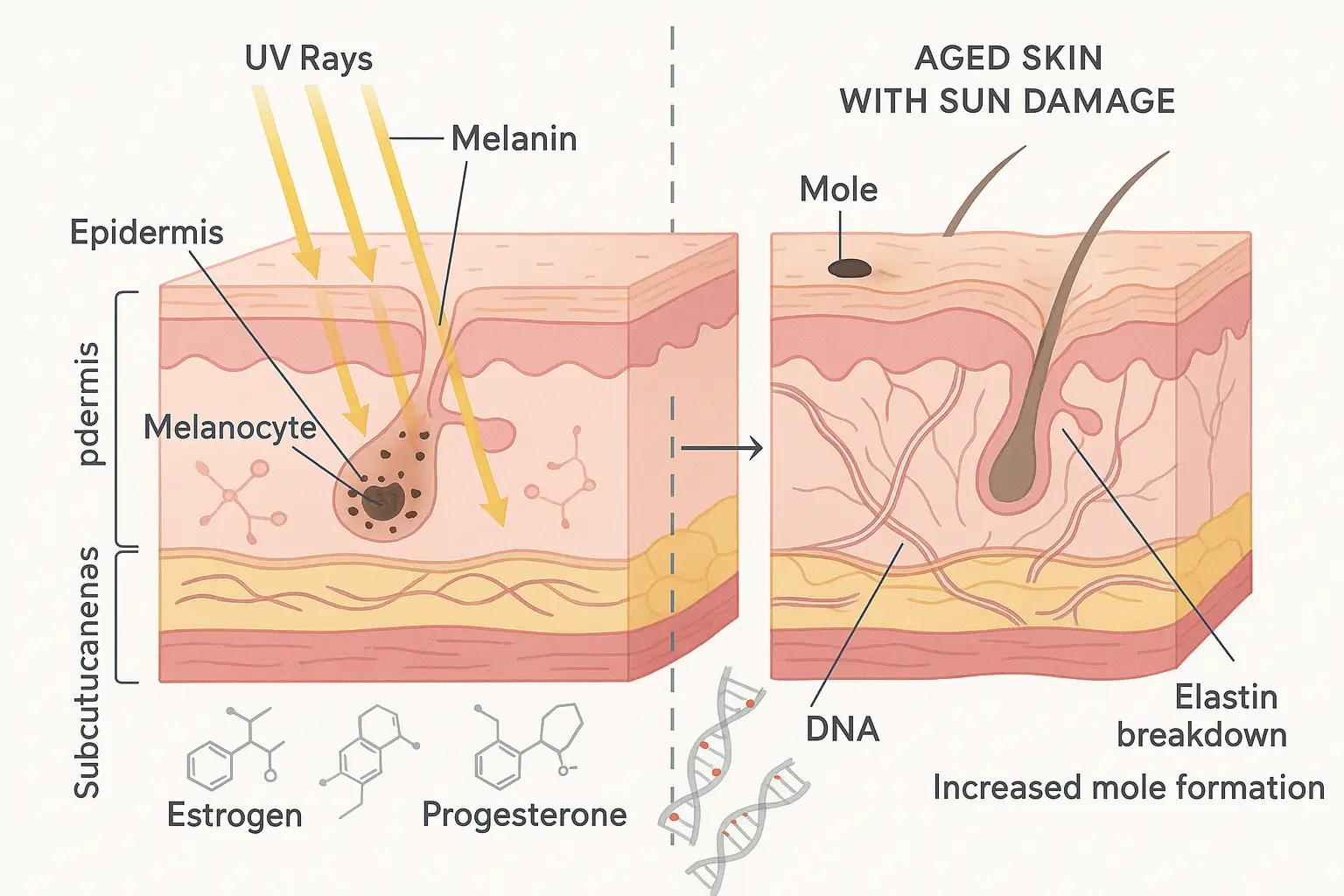

Before diving into why mole numbers increase with age, it's essential to understand what moles truly represent at a cellular level. Moles are benign (non-cancerous) growths that occur when melanocytes—the cells responsible for producing the pigment melanin—grow in clusters rather than spreading evenly throughout the skin.

Melanocytes are specialized cells located in the basal layer of the epidermis (the skin's outermost layer). Their primary function is to produce melanin, the pigment that gives skin, hair, and eyes their color. Melanin also serves as the body's natural defense mechanism against ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun.

In normal skin, melanocytes distribute evenly, creating uniform skin tone. However, when these cells cluster together, they form the concentrated pigmented spots we recognize as moles. These clusters can occur at different depths within the skin:

Not all moles are created equal. Understanding the various types helps explain why some appear at different life stages:

Mole TypeCharacteristicsTypical Age of AppearanceCongenital NeviPresent at birth, varying sizesBirthAcquired NeviDevelop after birth, most common typeChildhood through age 40Atypical (Dysplastic) NeviIrregular borders, multiple colors, larger sizeAdolescence onwardSpitz NeviPink or red, dome-shaped, rapid growthChildhood and adolescenceBlue NeviDeep blue or blue-black colorAdolescence and adulthood

For more information about different skin lesions, visit our comprehensive guide on 25 types of skin lesions explained.

The single most significant factor in developing new moles as we age is cumulative sun exposure. This isn't just about the sunburns from last summer's vacation—it's the total lifetime accumulation of UV radiation your skin has absorbed since childhood.

When UV rays penetrate the skin, they cause DNA damage in skin cells, including melanocytes. The body attempts to repair this damage, but the repair process isn't always perfect. Over time, repeated UV exposure can lead to:

Research published in dermatology journals indicates that approximately 90% of moles that develop after age 30 are directly linked to sun exposure patterns established earlier in life [1]. This explains why new moles can appear decades after significant sun exposure occurred.

Your skin has a remarkable but concerning ability to "remember" sun damage. Severe sunburns during childhood and adolescence create lasting cellular changes that may not manifest as visible moles until 10, 20, or even 30 years later. This delayed response occurs because:

Different patterns of sun exposure correlate with different mole characteristics:

Chronic continuous exposure (outdoor workers, athletes):

Intermittent intense exposure (occasional beachgoers, vacation sunbathers):

Understanding your personal sun exposure history is crucial for assessing mole development risk and determining appropriate monitoring schedules with a dermatologist at a specialized skin cancer clinic.

While sun exposure plays a starring role in mole development, genetics writes the script. Your DNA determines not only how many moles you're likely to develop throughout life but also how your skin responds to UV radiation.

Studies involving twins and families have revealed that genetics account for approximately 50-60% of the variation in mole count between individuals [2]. If your parents had numerous moles, you're statistically more likely to develop them as well, regardless of sun exposure.

Key genetic factors include:

MC1R gene variants: This gene regulates melanin production and skin pigmentation. Certain variants are strongly associated with:

CDKN2A gene mutations: Found in families with high melanoma rates, this gene affects cell growth regulation and significantly increases both mole development and cancer risk.

Other susceptibility genes: Research continues to identify additional genetic markers associated with mole-prone skin, including variations in genes controlling cell division and pigmentation.

The Fitzpatrick skin type classification system helps predict mole development patterns:

Fitzpatrick TypeCharacteristicsMole Development RiskType IVery fair, always burns, never tansHighest risk, most molesType IIFair, usually burns, tans minimallyHigh risk, many molesType IIIMedium, sometimes burns, gradually tansModerate riskType IVOlive, rarely burns, tans easilyLower risk, fewer molesType VBrown, very rarely burnsLow riskType VIDark brown/black, never burnsLowest risk, fewest moles

People with Types I and II skin not only develop more moles but also continue developing new ones later in life compared to those with darker skin types.

Some families carry genetic mutations that dramatically increase both mole numbers and melanoma risk. FAMMM syndrome characteristics include:

Individuals with FAMMM syndrome require more frequent professional skin examinations and heightened vigilance for changes. If you have a strong family history of moles or melanoma, consulting with specialists at The Minor Surgery Center can provide personalized monitoring strategies.

Beyond fixed genetic code, epigenetic changes—modifications in how genes are expressed without altering DNA sequence—also influence mole development. These changes can occur due to:

Epigenetic modifications help explain why identical twins with the same DNA can have different numbers of moles, and why mole development patterns can vary even among siblings with similar sun exposure histories.

Hormones act as powerful regulators of melanocyte activity, explaining why mole development often correlates with specific life stages characterized by hormonal shifts. Understanding these connections helps explain seemingly sudden appearances of new moles during certain periods.

The teenage years represent a peak period for mole development, with most people developing the majority of their lifetime moles between ages 10 and 25. This surge correlates directly with:

Increased hormone production:

Melanocyte stimulation:

Combined with sun exposure:

Pregnancy represents one of the most dramatic hormonal shifts in a woman's life, and moles often respond noticeably. Common pregnancy-related mole changes include:

New mole appearance: Many women develop new moles during pregnancy, particularly in the second and third trimesters when hormone levels peak.

Darkening of existing moles: Increased melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH) and estrogen can cause existing moles to become darker and more prominent.

Size increases: Some moles may grow larger due to hormonal stimulation, though dramatic changes should always be evaluated by a healthcare provider.

Pregnancy-specific lesions: Some pigmented spots that appear during pregnancy aren't true moles but rather temporary hormonal pigmentation changes that may fade postpartum.

Important Note: While mole changes during pregnancy are common and usually benign, any rapidly changing, bleeding, or concerning moles should be promptly evaluated, as pregnancy doesn't prevent melanoma development.

The perimenopausal and menopausal transition brings another wave of hormonal fluctuation that can affect mole behavior:

Estrogen decline effects:

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT):

Age-related changes:

Beyond the major life transitions, other hormonal factors affect mole development:

Oral contraceptives: Birth control pills may stimulate mole development in some women due to synthetic hormone exposure.

Thyroid disorders: Both hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism can affect skin pigmentation and mole characteristics.

Adrenal conditions: Disorders affecting cortisol and other adrenal hormones may influence melanocyte activity.

Stress hormones: Chronic elevated cortisol levels may indirectly affect mole development through immune system and inflammatory pathway changes.

Beyond sun damage, genetics, and hormones, the natural aging process itself creates conditions favorable for mole development. Understanding these age-related changes provides insight into why mole numbers tend to increase through middle age before plateauing.

As skin ages, several cellular changes occur that promote mole development:

Reduced DNA repair capacity: Aging cells become less efficient at repairing UV-induced DNA damage, allowing mutations to accumulate in melanocytes.

Senescent cell accumulation: Damaged cells that should die instead persist in a "zombie" state, potentially forming moles or causing neighboring cells to behave abnormally.

Immune system changes: The aging immune system becomes less effective at identifying and eliminating abnormal melanocyte clusters before they become visible moles.

Stem cell exhaustion: Melanocyte stem cells accumulate damage over decades, producing more abnormal daughter cells that cluster into moles.

Mole development follows a predictable pattern across the lifespan:

Birth to Age 10:

Ages 10-25:

Ages 25-40:

Ages 40-60:

Age 60+:

Interestingly, most people stop developing new moles after age 40-50. This plateau occurs because:

However, any new mole appearing after age 40 deserves professional evaluation, as melanomas can mimic benign moles, and new pigmented lesions in older adults have a higher probability of being malignant.

While most moles remain harmless throughout life, distinguishing between normal age-related mole changes and potential melanoma is crucial. Knowing what to look for empowers proactive skin health management.

Dermatologists use the ABCDE system to identify potentially problematic moles:

A - Asymmetry: Benign moles are typically symmetrical. If you draw a line through the middle, both halves should match. Asymmetrical moles warrant evaluation.

B - Border: Normal moles have smooth, well-defined borders. Irregular, notched, scalloped, or blurred edges are warning signs.

C - Color: Uniform color (brown, tan, or black) is normal. Multiple colors within one mole—especially red, white, blue, or mixed shades—require assessment.

D - Diameter: While not absolute, moles larger than 6mm (pencil eraser size) should be monitored more closely. However, melanomas can be smaller.

E - Evolution: Any mole that changes in size, shape, color, elevation, or develops new symptoms (itching, bleeding, crusting) needs professional evaluation.

For detailed information about identifying concerning skin changes, explore our guide on 4 types of skin cancer.

Beyond ABCDE, watch for:

Not all mole changes indicate cancer. Normal age-related changes include:

✅ Gradual lightening: Many moles fade with age, particularly after age 60

✅ Slight size fluctuation: Minor changes with weight gain/loss or hormonal shifts

✅ Pregnancy darkening: Temporary darkening during pregnancy that stabilizes postpartum

✅ Texture changes: Some moles become slightly more raised or develop a rougher texture with age

✅ Hair growth: Hair growing from a mole is actually a reassuring sign, as melanomas rarely grow hair

Certain factors increase the likelihood that a mole might become cancerous:

If you have multiple risk factors, establishing care with a specialized melanoma clinic ensures appropriate monitoring.

Given the complex factors influencing mole development with age, professional skin examinations become increasingly important. Knowing when and how often to seek evaluation can literally save lives.

Dermatological organizations provide the following general guidelines:

Average risk individuals:

Higher risk individuals (fair skin, high mole count, family history):

Highest risk (FAMMM syndrome, previous melanoma):

A comprehensive skin examination at a facility like The Minor Surgery Center typically includes:

Visual inspection: Full-body examination under good lighting, including scalp, between toes, and other easily overlooked areas

Dermoscopy: Use of a specialized magnifying device that illuminates skin structures invisible to the naked eye, improving melanoma detection accuracy by 20-30%

Documentation: Photography of concerning moles for comparison at future visits

Risk assessment: Discussion of personal and family history, sun exposure patterns, and other risk factors

Education: Guidance on proper self-examination techniques and warning signs

Biopsy if needed: Removal of suspicious moles for laboratory analysis

For residents in specific areas, specialized services are available at our Ajax and Barrie locations.

Monthly self-examinations complement professional screening:

Preparation:

Systematic approach:

Documentation:

Don't wait for a routine screening if you notice:

Early detection dramatically improves melanoma outcomes, with 5-year survival rates exceeding 99% for localized disease caught early [4].

While you can't change your genetics or reverse past sun damage, you can significantly reduce future mole development and melanoma risk through evidence-based prevention strategies.

Comprehensive sun protection remains the cornerstone of mole prevention:

Broad-spectrum sunscreen:

Protective clothing:

Behavioral modifications:

Emerging research suggests certain nutrients may provide additional photoprotection:

Topical antioxidants:

Dietary antioxidants:

While antioxidants provide supplementary benefits, they never replace proper sun protection measures.

Beyond direct sun protection, overall lifestyle choices affect skin cancer risk:

Avoid smoking: Smoking impairs skin's ability to repair UV damage and increases squamous cell carcinoma risk

Maintain healthy weight: Obesity is associated with increased melanoma risk and worse outcomes

Limit alcohol: Excessive alcohol consumption may increase melanoma risk, though research is ongoing

Manage stress: Chronic stress impairs immune function, potentially reducing the body's ability to eliminate abnormal cells

Prioritize sleep: Quality sleep supports cellular repair processes and immune function

If you have significant risk factors, additional strategies may be appropriate:

Chemoprevention: Some high-risk individuals may benefit from medications like nicotinamide (vitamin B3), which has shown promise in reducing skin cancer rates in certain populations [5]

Enhanced surveillance: Consider total body photography and digital dermoscopy for tracking subtle changes

Genetic counseling: For those with strong family histories or FAMMM syndrome

Prophylactic removal: In some cases, removing atypical moles may be recommended, though this remains controversial and individualized

When moles require removal—whether for medical concerns or cosmetic reasons—several treatment options exist, each with specific indications and advantages.

Moles should be removed when they:

Surgical excision:

Shave removal:

Punch biopsy:

Laser removal:

For professional mole removal with comprehensive pathological examination, facilities like The Minor Surgery Center offer specialized services with experienced practitioners.

Immediate post-procedure:

Healing timeline:

Pathology results:

For optimal cosmetic outcomes after mole removal:

Separating fact from fiction helps make informed decisions about mole management.

Myth: "Cutting or irritating a mole causes cancer" Reality: While you shouldn't deliberately injure moles, physical trauma doesn't transform benign moles into melanoma. However, repeatedly traumatized moles may warrant removal for practical reasons.

Myth: "Hair growing from a mole means it's cancerous" Reality: The opposite is true. Hair growth from a mole is actually reassuring, as melanomas rarely produce hair follicles.

Myth: "All moles eventually become cancerous if you live long enough" Reality: The vast majority of moles remain benign throughout life. Only a tiny fraction ever transform into melanoma.

Myth: "Removing a mole prevents cancer" Reality: Prophylactically removing normal moles doesn't reduce melanoma risk, as most melanomas arise from previously normal skin, not existing moles.

Myth: "Dark-skinned people don't need to worry about moles or melanoma" Reality: While melanoma is less common in darker skin types, it does occur and is often diagnosed at later, more dangerous stages. Everyone should monitor their skin regardless of complexion.

Myth: "Sunscreen prevents vitamin D deficiency, so you need sun exposure without protection" Reality: Brief incidental sun exposure provides adequate vitamin D for most people. If concerned, vitamin D supplementation is safer than unprotected UV exposure.

Myth: "Once you're older, sun damage is done and protection doesn't matter" Reality: Sun protection benefits occur at any age. Even after significant cumulative damage, continued protection reduces further damage and allows some repair mechanisms to function.

Myth: "Tanning beds are safer than natural sun for getting a base tan" Reality: Tanning beds emit concentrated UV radiation and are classified as Group 1 carcinogens. There is no such thing as a "safe" or "healthy" tan from any UV source.

Technological advances are revolutionizing how we monitor moles and detect melanoma earlier than ever before.

Machine learning algorithms trained on millions of dermoscopic images can now:

While AI tools show tremendous promise, they currently serve as decision support rather than replacement for clinical expertise. For information about the reliability of various technologies, see our article on 3D mole mapping apps.

Advanced imaging systems now allow:

These technologies are particularly valuable for individuals with numerous moles, making comprehensive monitoring feasible.

Emerging genetic tests can:

Research continues on technologies that may one day diagnose melanoma without biopsy:

While promising, these technologies currently complement rather than replace traditional biopsy for definitive diagnosis.

Researchers are developing blood tests that detect:

These "liquid biopsies" may eventually enable screening for melanoma before lesions become visible, though significant development remains before clinical application.

Understanding Why We Get More Moles As We Age: Sun Damage, Hormones, and Genetics Explained empowers proactive management of skin health throughout life. While you cannot change genetic predisposition or reverse past sun exposure, you absolutely can influence future mole development and melanoma risk through informed choices and vigilant monitoring.

Assess your personal risk: Consider your skin type, family history, sun exposure patterns, and current mole count to understand your baseline risk level.

Establish a monitoring routine: Implement monthly self-examinations using the ABCDE criteria and systematic full-body approach. Document concerning moles with photographs and notes.

Schedule professional screening: If you haven't had a comprehensive skin examination, schedule one today—particularly if you're over 40, have numerous moles, or have other risk factors. Contact The Minor Surgery Center to arrange a thorough evaluation.

Optimize sun protection: Commit to daily broad-spectrum sunscreen use, protective clothing, and behavioral modifications that minimize UV exposure. Remember: it's never too late to benefit from sun protection.

Address concerning changes promptly: Don't adopt a "wait and see" approach with changing moles. Early detection saves lives, and professional evaluation provides peace of mind.

Educate family members: Share information about mole monitoring with children, siblings, and other relatives who may share genetic risk factors. Establishing good sun protection habits in children prevents future mole development.

Stay informed: Skin cancer research evolves rapidly. Periodically review updated guidelines and emerging technologies that may benefit your specific situation. Visit our blog for the latest information on skin health topics.

Moles are a natural part of skin biology, and developing new moles through middle age is common and usually benign. The interplay of cumulative sun damage, genetic predisposition, and hormonal influences creates individual patterns of mole development that vary widely between people.

However, this natural process requires informed vigilance. The same factors that produce benign moles can also trigger melanoma—one of the most preventable yet potentially deadly cancers when caught late. By understanding your personal risk factors, implementing comprehensive sun protection, performing regular self-examinations, and maintaining appropriate professional screening, you transform from passive observer to active participant in your skin health.

Your skin tells the story of your life—sun-soaked beach vacations, outdoor adventures, genetic inheritance from parents and grandparents, and the hormonal journeys of growth, reproduction, and aging. By learning to read this story and respond appropriately to its chapters, you ensure that the narrative continues for many healthy years to come. 🌟

The appearance of new moles doesn't have to be a source of anxiety when paired with knowledge, appropriate monitoring, and access to expert care. Take control of your skin health journey today—your future self will thank you.

[1] Gandini, S., et al. (2005). "Meta-analysis of risk factors for cutaneous melanoma: II. Sun exposure." European Journal of Cancer, 41(1), 45-60.

[2] Wachsmuth, R. C., et al. (2001). "Heritability and gene-environment interactions for melanocytic nevus density examined in a U.K. adolescent twin study." Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 117(2), 348-352.

[3] Gandini, S., et al. (2005). "Meta-analysis of risk factors for cutaneous melanoma: I. Common and atypical naevi." European Journal of Cancer, 41(1), 28-44.

[4] American Cancer Society. (2025). "Survival Rates for Melanoma Skin Cancer by Stage." Cancer Statistics Center.

[5] Chen, A. C., et al. (2015). "A Phase 3 Randomized Trial of Nicotinamide for Skin-Cancer Chemoprevention." New England Journal of Medicine, 373(17), 1618-1626.