Every person has moles scattered across their skin, but knowing which ones deserve attention can literally save a life. While most moles remain harmless throughout a lifetime, some transform into dangerous melanoma—the deadliest form of skin cancer. Understanding the visual differences between normal, precancerous, and cancerous moles empowers individuals to detect warning signs early, when treatment success rates exceed 99%. This comprehensive Normal vs Precancerous vs Cancerous Moles: A Side-by-Side Picture Guide provides the visual literacy and medical knowledge needed to protect skin health through informed self-examination and timely professional evaluation.

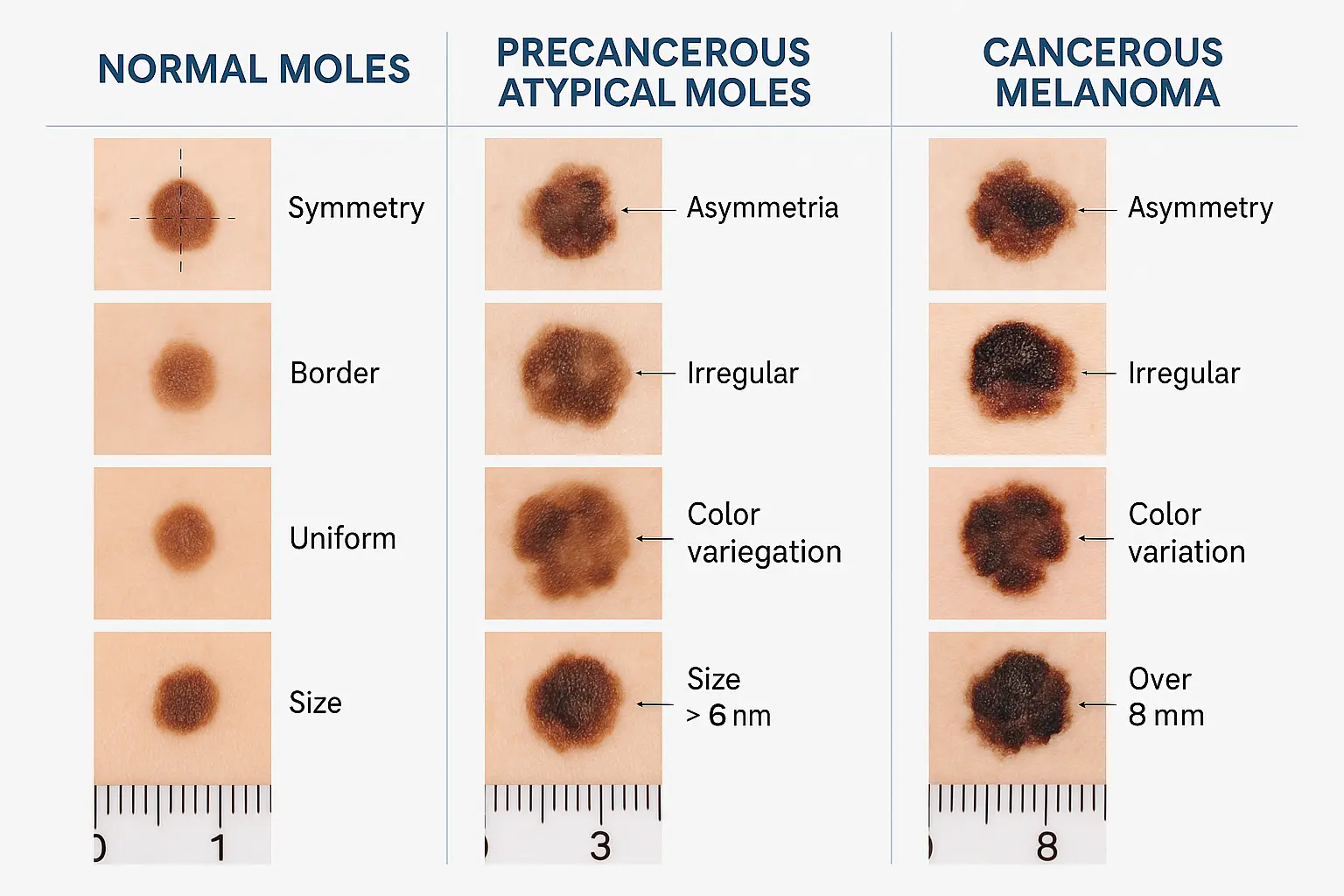

✅ Normal moles are symmetrical, have smooth borders, display uniform color (typically one shade of brown), measure less than 6mm in diameter, and remain stable over time

✅ Precancerous (atypical) moles exhibit irregular features including asymmetry, notched borders, mixed colors, larger size (over 6mm), and require professional monitoring to prevent melanoma development

✅ Cancerous moles (melanoma) display the ABCDE warning signs: Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Color variation, Diameter greater than 6mm, and Evolving characteristics that change over weeks or months

✅ The "Ugly Duckling" sign—a mole that looks distinctly different from surrounding moles—serves as a critical red flag requiring immediate dermatological evaluation

✅ Early detection through monthly self-examinations and annual professional skin checks dramatically improves melanoma survival rates, making visual recognition skills essential for everyone

Moles, medically termed nevi (singular: nevus), represent clusters of pigment-producing cells called melanocytes that group together in the skin. Most people develop between 10 and 40 moles throughout their lifetime, with the majority appearing during childhood and young adulthood[1]. These common skin growths serve as normal features of human skin, but their characteristics provide crucial information about potential health risks.

Normal moles share several consistent characteristics that distinguish them from problematic lesions. Understanding these baseline features creates the foundation for recognizing abnormalities. Typical benign moles exhibit:

Normal moles typically develop during the first two decades of life, though some may appear later[2]. They can be flat or slightly raised, with smooth or minimally textured surfaces. The color remains consistent throughout the mole, without variations or multiple hues within a single lesion.

Not all moles fit into simple categories. The spectrum ranges from completely benign congenital nevi (present at birth) to acquired moles (developing later in life) to atypical dysplastic nevi that occupy the middle ground between normal and cancerous. Understanding this continuum helps contextualize the Normal vs Precancerous vs Cancerous Moles: A Side-by-Side Picture Guide framework.

Congenital nevi appear at birth and affect approximately 1% of newborns[3]. While most remain benign, larger congenital nevi (especially those exceeding 20cm) carry slightly elevated melanoma risk and warrant professional monitoring throughout life.

Acquired nevi develop after birth, typically during childhood and adolescence. These represent the most common mole type and generally pose minimal cancer risk when they maintain stable, normal characteristics.

Atypical (dysplastic) nevi exhibit some abnormal features without meeting full melanoma criteria. These precancerous moles require careful monitoring, as individuals with multiple atypical moles face increased melanoma risk[4]. For more information about different skin lesions, visit our comprehensive guide on 25 types of skin lesions.

The ABCDE rule provides a standardized framework for evaluating moles and identifying potential melanoma. This medically validated system empowers individuals to conduct effective self-examinations and recognize warning signs that warrant professional evaluation. Each letter represents a distinct characteristic that, when present, suggests increased cancer risk.

Asymmetry represents one of the most reliable early indicators of melanoma. To assess this characteristic, imagine drawing a line through the center of a mole. In normal moles, both halves mirror each other almost perfectly—they match in shape, size, and appearance. Cancerous moles typically fail this symmetry test, with one half looking noticeably different from the other[5].

Normal mole asymmetry: Both halves match when mentally divided Precancerous mole asymmetry: Slight irregularity in shape, but generally balanced Cancerous mole asymmetry: Distinct differences between halves, with irregular growth patterns

The border or edge of a mole provides critical diagnostic information. Healthy moles feature smooth, well-defined borders that create a clear boundary between the mole and surrounding skin. Problematic moles often display irregular edges that appear notched, scalloped, ragged, blurred, or poorly defined[6].

Border characteristics to evaluate:

Melanomas frequently exhibit borders that seem to "leak" into surrounding skin, with pigment appearing to spread beyond the main lesion. This indistinct boundary reflects the uncontrolled growth pattern characteristic of cancer cells.

Color variation within a single mole serves as a significant warning sign for melanoma. Normal moles typically display a single, uniform shade—whether tan, brown, or dark brown—throughout the entire lesion. Cancerous moles often present multiple colors within the same growth, including combinations of tan, brown, black, blue, red, white, or pink[7].

Color warning signs include:

The presence of multiple colors indicates abnormal melanocyte activity, with different pigment concentrations reflecting irregular cell behavior. This variation distinguishes potentially dangerous moles from benign pigmented lesions.

The diameter threshold of 6 millimeters (approximately the size of a pencil eraser) provides a useful screening guideline, though it should not be the sole determining factor. Melanomas often grow larger than this benchmark, but they can also begin at 1mm or smaller[8]. Size assessment works best when combined with other ABCDE criteria.

Important diameter considerations:

While larger moles statistically carry higher melanoma risk, dismissing small lesions based solely on size can delay critical diagnosis. Any mole displaying other concerning features deserves attention regardless of diameter.

The evolving characteristic represents perhaps the most critical element in the ABCDE framework. Melanomas change at a different rate than normal background moles, exhibiting transformation in size, shape, color, or symptoms over weeks to months[9]. Any mole that looks different from previous examinations or behaves differently from other moles warrants immediate professional assessment.

Evolution warning signs:

Documenting moles through regular photography enables effective change tracking. Monthly self-examinations combined with annual professional skin checks create a comprehensive monitoring system for detecting evolution early. Learn more about professional evaluation at our best skin cancer clinic.

Understanding what constitutes a normal, benign mole establishes the baseline for recognizing abnormalities. Most people develop numerous normal moles throughout their lifetime, and these harmless skin features require no treatment or intervention beyond routine monitoring.

Normal moles exhibit consistent, predictable features that distinguish them from precancerous and cancerous lesions. These characteristics include:

FeatureNormal Mole DescriptionShapeRound or oval with symmetrical appearanceBorderSmooth, even edges with clear definitionColorSingle uniform shade (pink, tan, brown, or dark brown)SizeTypically less than 6mm diameterSurfaceSmooth or slightly raised; may have fine hairsStabilityMinimal change over months and yearsDistributionScattered across body, often in sun-exposed areas

Several distinct types of benign moles appear commonly across different populations:

Junctional nevi appear flat and brown, located where the epidermis meets the dermis. These typically develop during childhood and adolescence, representing the most common mole type in younger individuals.

Compound nevi feature both flat and raised components, with pigment cells present in multiple skin layers. These often appear slightly elevated with uniform brown coloration and smooth borders.

Dermal nevi project above the skin surface, creating a dome-shaped appearance. These flesh-colored or light brown moles frequently develop facial hair and represent the most common mole type in adults.

Halo nevi display a white ring or "halo" of depigmented skin surrounding a central brown mole. While their appearance may seem concerning, halo nevi typically represent a benign immune response and often fade naturally over time[10].

Even benign-appearing moles warrant professional evaluation under certain circumstances:

For more detailed information about benign moles, explore our article on benign mole explained.

Precancerous moles, medically termed atypical nevi or dysplastic nevi, occupy the critical middle ground between completely benign lesions and frank melanoma. These abnormal moles exhibit some concerning features without meeting full criteria for cancer diagnosis, yet they signal increased melanoma risk and require vigilant monitoring[11].

Atypical moles display several distinguishing features that set them apart from both normal moles and melanoma:

Size: Typically larger than normal moles, often exceeding 6mm (one-quarter inch) in diameter, though smaller atypical moles can occur

Shape: Irregular or asymmetrical configuration, with one half not matching the other when mentally divided

Borders: Notched, fading, or poorly defined edges that blur into surrounding skin rather than maintaining sharp boundaries

Color: Mixed or varied pigmentation within a single lesion, displaying combinations of pink, red, tan, and brown hues

Surface: May appear slightly raised in the center with flatter edges, creating a "fried egg" appearance

Distribution: Can develop anywhere on the body, though commonly appear on the back, chest, and extremities

Some individuals develop atypical mole syndrome (also called dysplastic nevus syndrome), characterized by numerous atypical moles—sometimes 50 or more—scattered across the body[12]. This condition significantly elevates melanoma risk, particularly when combined with:

Individuals with atypical mole syndrome require more frequent professional skin examinations, typically every 3-6 months, along with diligent monthly self-checks and photographic documentation of lesions.

Precancerous moles demand proactive management to prevent melanoma development:

Professional surveillance: Dermatological examination every 6-12 months with dermoscopy (magnified examination) and baseline photography

Selective biopsy: Removal and pathological examination of the most concerning atypical moles to rule out early melanoma

Patient education: Training in effective self-examination techniques and recognition of changing characteristics

Risk factor modification: Sun protection strategies including broad-spectrum sunscreen, protective clothing, and sun avoidance during peak hours

Documentation: Regular photography of atypical moles to track subtle changes over time

The relationship between atypical moles and melanoma risk parallels other precancerous conditions. Similar to how actinic keratosis can progress to squamous cell carcinoma, atypical moles represent a warning sign that warrants increased vigilance and preventive action.

The Ugly Duckling sign provides an intuitive method for identifying concerning moles, including atypical lesions. This concept recognizes that most of a person's moles resemble each other—they're part of the same "family" with similar characteristics. A mole that looks distinctly different from surrounding moles—whether due to larger size, different color, more irregular shape, or unique features—represents the "ugly duckling" and warrants professional evaluation[13].

This pattern recognition approach complements the ABCDE rule, helping identify problematic moles that might not trigger individual ABCDE criteria but nonetheless appear abnormal within the context of a person's overall mole pattern. For comprehensive information about atypical moles, visit our detailed guide on atypical moles.

Melanoma represents the most dangerous form of skin cancer, accounting for the vast majority of skin cancer deaths despite comprising only about 1% of skin cancer cases[14]. However, when detected early—before spreading beyond the skin surface—melanoma is highly curable with five-year survival rates exceeding 99%[15]. This dramatic difference between early and late-stage outcomes makes visual recognition skills absolutely critical.

Melanoma manifests in several distinct forms, each with characteristic visual features:

The most common melanoma type (approximately 70% of cases), superficial spreading melanoma typically appears as a flat or slightly raised discolored patch with irregular borders and varied colors. It often develops from existing moles or appears as new lesions on sun-exposed skin[16].

Visual characteristics:

Nodular melanoma grows more rapidly than other types, appearing as a raised bump or nodule that may be black, blue-black, or occasionally red or skin-colored. This aggressive form accounts for 10-15% of melanomas and often lacks the typical ABCDE warning signs in early stages[17].

Visual characteristics:

Developing primarily in older adults with significant sun damage, lentigo maligna melanoma appears as a large, flat, tan or brown patch with darker areas and irregular borders. It typically occurs on chronically sun-exposed areas like the face, ears, and arms[18].

Visual characteristics:

Acral lentiginous melanoma develops on palms, soles, or under nails—areas not typically sun-exposed. This type represents the most common melanoma in individuals with darker skin tones[19]. For detailed information about this specific type, see our article on acral melanoma.

Visual characteristics:

Beyond the ABCDE criteria, several additional features suggest advanced or aggressive melanoma:

🔴 Bleeding or oozing from a mole without trauma 🔴 Crusting or scabbing that doesn't heal 🔴 Itching, tenderness, or pain in a previously asymptomatic mole 🔴 Rapid growth over weeks rather than months or years 🔴 Satellite lesions (smaller pigmented spots appearing near the main lesion) 🔴 Ulceration (breakdown of skin surface) 🔴 Firmness or hardness when touched

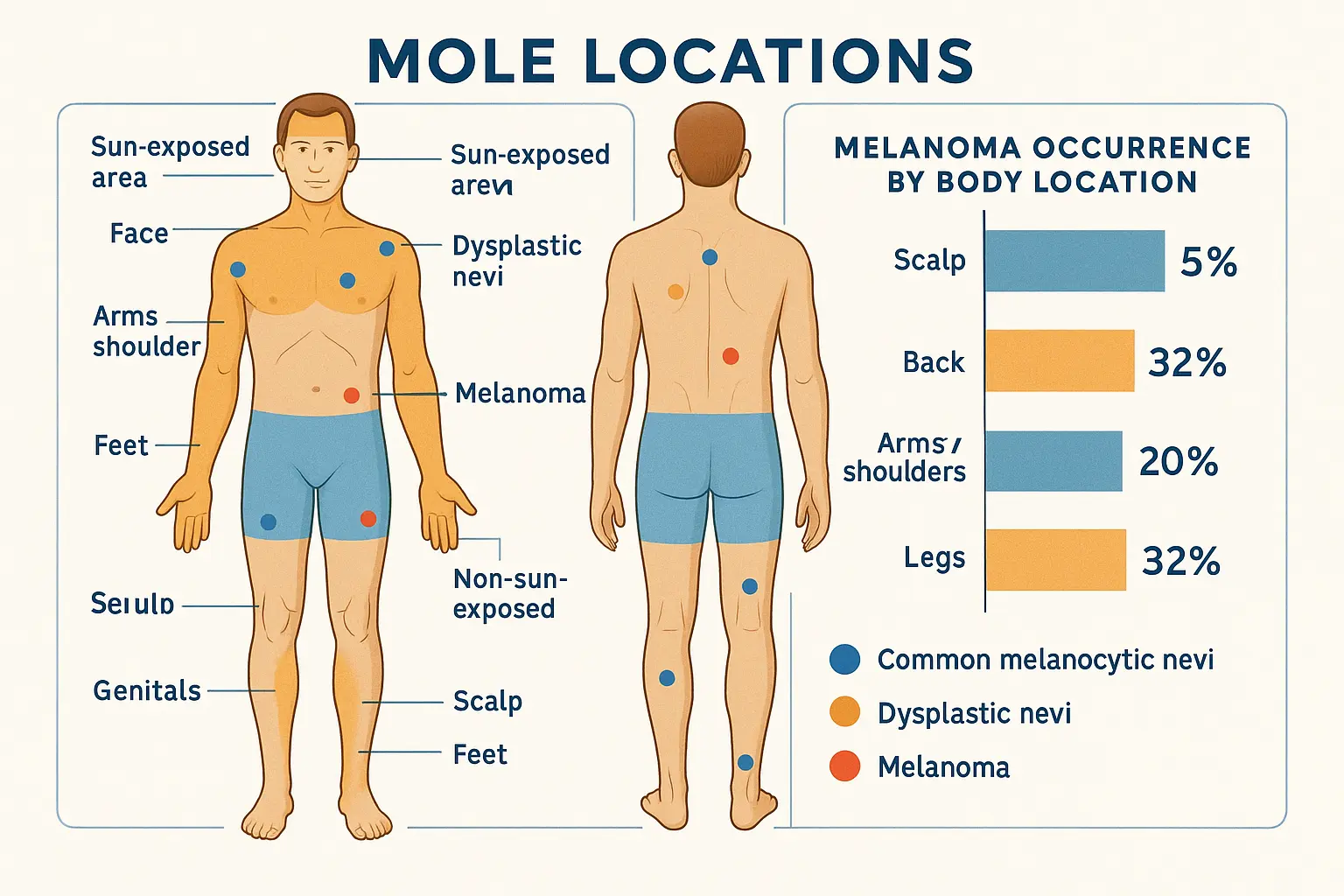

Melanoma can develop anywhere on the body, including areas rarely exposed to sunlight. Comprehensive skin examination should include:

This comprehensive approach ensures no potential melanoma escapes detection. For information about different skin cancer types, including melanoma, visit our guide on 4 types of skin cancer.

The stage at which melanoma is detected dramatically affects survival outcomes:

These statistics underscore why understanding the Normal vs Precancerous vs Cancerous Moles: A Side-by-Side Picture Guide framework can literally save lives. Early recognition enables treatment when melanoma remains most curable.

Monthly self-examination represents the cornerstone of early melanoma detection. While professional skin checks provide expert evaluation, most melanomas are initially discovered by patients or their family members[21]. Developing systematic self-examination skills empowers individuals to monitor their skin health proactively.

Effective self-examination requires proper preparation and tools:

Timing: Choose a consistent day each month (e.g., first day of the month) to establish routine

Lighting: Use bright, natural lighting when possible; supplement with a handheld lamp for detailed examination

Tools needed:

Environment: Select a private, well-lit room where you can examine your entire body comfortably

Follow this systematic approach to ensure complete skin coverage:

Step 1: Face and Scalp

Step 2: Upper Body (Front)

Step 3: Upper Body (Back)

Step 4: Lower Body

Step 5: Genital and Perianal Areas

Tracking moles over time enables effective change detection:

Photography: Take standardized photos of concerning moles monthly, using the same lighting, distance, and angle. Include a ruler or coin for size reference.

Body maps: Create simple diagrams marking mole locations, with notes describing characteristics of atypical or concerning lesions.

Journaling: Record dates of examinations, new findings, and changes observed. Note any symptoms like itching or bleeding.

Comparison: Review previous photos and notes during each examination to identify evolution.

Modern technology offers additional support through smartphone apps designed for mole tracking and monitoring. However, these tools supplement rather than replace professional evaluation. For information about the reliability of these technologies, see our article on 3D mole mapping apps.

Self-examination should prompt professional consultation when you observe:

✋ Any mole displaying ABCDE warning signs ✋ The "ugly duckling" sign—a mole looking different from others ✋ New moles developing after age 30 ✋ Existing moles changing in size, color, or shape ✋ Moles causing symptoms (itching, bleeding, tenderness) ✋ Any lesion causing concern, even without specific warning signs

Trust your instincts. If something seems wrong with a mole, seek professional evaluation. Early consultation poses no downside, while delayed diagnosis can prove fatal.

When self-examination or routine screening identifies concerning moles, professional evaluation provides definitive diagnosis and appropriate treatment. Understanding the diagnostic process and treatment options helps patients navigate the healthcare system effectively and make informed decisions.

Dermatological examination involves systematic visual inspection of the entire skin surface, often supplemented by dermoscopy—magnified examination using a specialized instrument called a dermatoscope[22]. This tool enables visualization of subsurface skin structures and pigment patterns invisible to the naked eye, improving diagnostic accuracy.

During professional examination, dermatologists assess:

Dermatologists may photograph concerning lesions for documentation and future comparison, creating a baseline for tracking changes over time.

When a mole appears suspicious, biopsy—removal of tissue for microscopic examination—provides definitive diagnosis. Several biopsy techniques exist:

Excisional biopsy: Complete removal of the entire lesion with a margin of normal-appearing skin. This represents the gold standard for suspected melanoma, as it enables complete pathological assessment and often serves as both diagnostic and therapeutic intervention.

Punch biopsy: Removal of a cylindrical core of tissue using a circular blade. This technique works well for sampling larger lesions or when complete excision isn't immediately feasible.

Shave biopsy: Horizontal removal of the lesion's raised portion using a blade. While quick and simple, this technique may not remove sufficient depth for accurate melanoma staging and is generally avoided for suspected melanoma.

The removed tissue undergoes pathological examination, where a specialized physician (pathologist) examines cellular characteristics under microscopy to determine whether the lesion is benign, precancerous, or malignant[23].

Treatment approaches vary based on diagnosis:

Benign moles typically require no treatment beyond monitoring. However, removal may be recommended for:

Removal methods include surgical excision or shave removal, depending on the mole's characteristics and location. These procedures are typically performed in-office under local anesthesia.

Precancerous moles may be removed completely or monitored closely depending on their characteristics and the patient's overall risk profile. Management options include:

Complete excision: Surgical removal with clear margins to eliminate the atypical cells and prevent potential progression to melanoma

Close monitoring: Regular professional examinations (every 3-6 months) with dermoscopy and photography for stable atypical moles in low-risk patients

Selective removal: Excision of the most concerning atypical moles while monitoring others

The decision between removal and monitoring considers factors including the degree of atypia, number of atypical moles, family history, and patient preference.

Melanoma treatment depends on the stage and characteristics of the cancer:

Stage 0 and Stage I: Wide excision (complete removal with margins of normal tissue) often provides curative treatment. The margin width depends on melanoma thickness, typically ranging from 0.5cm to 2cm[24].

Stage II: Wide excision plus consideration of sentinel lymph node biopsy to determine if cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes. Some patients may benefit from adjuvant immunotherapy or targeted therapy.

Stage III: Wide excision, lymph node removal, and systemic therapy (immunotherapy or targeted therapy) to reduce recurrence risk.

Stage IV: Systemic treatment including immunotherapy, targeted therapy, or clinical trials. Surgery may be used for symptom management or removal of isolated metastases.

For more information about melanoma stages and treatment, see our article on advanced melanoma stages.

Selecting an experienced healthcare provider ensures optimal outcomes. Consider these factors:

Board certification: Choose dermatologists certified by the American Board of Dermatology or equivalent national board

Melanoma experience: For confirmed or suspected melanoma, seek providers with specific melanoma expertise

Surgical skills: Complex melanoma cases may require surgical oncologists or plastic surgeons with melanoma training

Multidisciplinary care: Advanced melanoma benefits from team-based care including medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, and pathologists

Communication style: Select providers who listen to concerns, explain options clearly, and involve patients in decision-making

For expert evaluation and treatment, consider visiting The Minor Surgery Center, which specializes in comprehensive skin lesion assessment and treatment. Our locations in Ajax and Barrie offer accessible, expert care for mole evaluation and removal.

While genetic factors influence melanoma risk, prevention strategies can significantly reduce the likelihood of developing skin cancer. Comprehensive sun protection and risk-aware behaviors form the foundation of melanoma prevention.

Ultraviolet (UV) radiation from sunlight represents the primary modifiable risk factor for melanoma[25]. Effective sun protection includes:

Tanning beds emit concentrated UV radiation and significantly increase melanoma risk. Studies show that tanning bed use before age 35 increases melanoma risk by 75%[26]. Complete avoidance of indoor tanning represents a critical prevention strategy, particularly for young people.

Certain individuals face elevated melanoma risk and require enhanced prevention and surveillance:

High-risk characteristics:

Enhanced strategies for high-risk individuals:

While sun protection reduces melanoma risk, concerns about vitamin D deficiency sometimes arise. However, most dermatologists and oncologists recommend obtaining vitamin D through diet and supplements rather than sun exposure, as the skin cancer risks outweigh potential vitamin D benefits[27].

Vitamin D sources:

Comprehensive melanoma prevention extends beyond sun protection to include:

Regular skin examinations: Monthly self-checks and annual professional evaluations

Risk awareness: Understanding personal risk factors and family history

Education: Learning to recognize warning signs and teaching family members

Prompt evaluation: Seeking professional assessment for concerning changes without delay

Lifestyle modifications: Avoiding tanning beds, practicing sun protection, and maintaining overall health

These strategies work synergistically to reduce melanoma risk while enabling early detection when prevention fails. For additional information about building skin-healthy habits, explore our article on building a skin-healthy lifestyle.

Melanoma risk and presentation vary across different populations, requiring tailored awareness and screening approaches. Understanding these variations ensures appropriate vigilance across all demographic groups.

While pediatric melanoma remains rare, accounting for less than 2% of all melanoma cases, it does occur and presents unique challenges[28]. Children and adolescents may develop melanoma with atypical features that don't follow standard ABCDE criteria.

Pediatric melanoma characteristics:

Screening recommendations for children:

Elderly individuals face increased melanoma risk due to cumulative sun exposure and age-related immune changes. Melanoma in older adults often presents as lentigo maligna melanoma on chronically sun-damaged skin.

Considerations for older adults:

Individuals with darker skin face lower overall melanoma risk but experience worse outcomes when melanoma develops, primarily due to delayed diagnosis[29]. Melanoma in darker-skinned individuals often presents in atypical locations and with different characteristics.

Key differences in darker skin:

Screening emphasis for darker skin tones:

Amelanotic melanoma—melanoma lacking typical dark pigmentation—represents approximately 2-8% of melanomas and poses diagnostic challenges[30]. These lesions may appear pink, red, or skin-colored, resembling benign conditions.

Amelanotic melanoma features:

Pregnancy doesn't increase melanoma risk, but existing moles may darken or change due to hormonal influences. Additionally, melanoma diagnosed during pregnancy presents unique management challenges.

Pregnancy considerations:

Understanding the Normal vs Precancerous vs Cancerous Moles: A Side-by-Side Picture Guide framework becomes clearer with direct comparison. The following tables summarize key distinguishing features across mole types.

FeatureNormal MolesPrecancerous (Atypical) MolesCancerous Moles (Melanoma)SymmetrySymmetrical—both halves matchSlightly asymmetricalMarkedly asymmetricalBorderSmooth, well-defined edgesIrregular, notched, or fading bordersRagged, scalloped, blurred, or poorly definedColorSingle uniform shade (pink, tan, brown)Mixed colors (pink, red, tan, brown)Multiple distinct colors (brown, black, red, white, blue, pink)DiameterUsually < 6mmOften > 6mm (but can be smaller)Typically > 6mm (but can start smaller)EvolutionStable over timeMay change slowlyChanges noticeably over weeks to monthsSurfaceSmooth or slightly raisedMay have "fried egg" appearanceMay be raised, rough, scaly, bleeding, or crustingDistributionScattered across bodyCan appear anywhere; often multipleCan appear anywhere, including unusual locations

AspectNormal MolesPrecancerous (Atypical) MolesCancerous Moles (Melanoma)Cancer RiskMinimalIncreased risk; marker for melanoma susceptibilityIs cancer; requires immediate treatmentMonitoring FrequencyAnnual professional exam; monthly self-checkEvery 3-6 months professional; monthly self-checkImmediate evaluation and treatmentTreatment NeedOptional (cosmetic or irritation)Selective removal or close monitoringMandatory surgical excision with marginsBiopsy IndicationRarely needed unless changingRecommended for most concerning lesionsAlways required for diagnosis and stagingFollow-upRoutine screeningRegular monitoring; increased surveillanceIntensive follow-up based on stagePrevention FocusSun protectionEnhanced sun protection; regular screeningSecondary prevention (early detection)

SymptomNormal MolesPrecancerous (Atypical) MolesCancerous Moles (Melanoma)ItchingRare; usually from irritationUncommonMay occurBleedingOnly from traumaRareMay occur spontaneouslyTendernessOnly when irritatedUncommonMay occurCrustingRareRareMay occurOozingNoNoMay occur in advanced lesionsSatellite LesionsNoNoMay occur (sign of spreading)

Conduct monthly self-examinations and schedule annual professional skin checks with a dermatologist. Individuals with high melanoma risk (family history, numerous atypical moles, previous melanoma) should have professional examinations every 3-6 months.

Yes. Approximately 70-80% of melanomas develop as new lesions rather than from existing moles[31]. This underscores the importance of monitoring for new moles, especially after age 30, and not focusing exclusively on existing moles.

Schedule a dermatology appointment promptly—ideally within 1-2 weeks for clearly suspicious lesions. Document the mole with photographs and note when you first noticed it or what changes occurred. Avoid attempting self-removal, as this can interfere with diagnosis and potentially spread cancer cells if melanoma is present.

Not necessarily. Both raised and flat moles can be benign or malignant. The ABCDE characteristics matter more than whether a mole is raised or flat. However, a previously flat mole that becomes raised warrants evaluation, as this represents evolution (the "E" in ABCDE).

While you cannot completely prevent mole development (which is largely genetic), sun protection can reduce the number of acquired moles and prevent existing moles from becoming atypical or cancerous. Consistent sunscreen use, sun avoidance, and protective clothing help minimize UV-induced changes.

No. While the ABCDE rule identifies most melanomas, some exceptions exist. Nodular melanoma may appear symmetrical and uniform in color. Amelanotic melanoma lacks pigmentation. The "ugly duckling" sign helps identify these atypical presentations. Any changing or concerning lesion deserves evaluation regardless of ABCDE criteria.

Absolutely not. Home mole removal carries serious risks including infection, scarring, incomplete removal, and delayed melanoma diagnosis. If melanoma is present, incomplete removal can spread cancer cells. Always have moles removed by qualified healthcare professionals who can ensure complete excision and pathological examination.

Smartphone apps for mole assessment show variable accuracy and should never replace professional evaluation[32]. While these tools can help with documentation and tracking changes, they cannot definitively diagnose or rule out melanoma. Use them as supplementary tools for monitoring, but always seek professional evaluation for concerning moles.

If biopsy confirms melanoma, your dermatologist will determine the stage based on thickness, ulceration, and other factors. You'll likely undergo wider excision to remove additional surrounding tissue with clear margins. Depending on the stage, you may need sentinel lymph node biopsy, imaging studies, and potentially systemic therapy. Early-stage melanoma has excellent prognosis with appropriate treatment.

Yes. Advanced melanoma can metastasize (spread) to lymph nodes, lungs, liver, brain, and other organs. However, melanoma detected and treated early—before it grows deep into the skin or spreads—is highly curable. This makes early detection through mole monitoring absolutely critical.

Understanding the Normal vs Precancerous vs Cancerous Moles: A Side-by-Side Picture Guide framework provides essential knowledge for protecting skin health and potentially saving lives. The visual differences between benign moles, atypical precancerous lesions, and melanoma—while sometimes subtle—become recognizable with education and practice.

The key principles to remember include:

🔍 Regular monitoring matters: Monthly self-examinations combined with annual professional skin checks create a comprehensive surveillance system that enables early detection when treatment is most effective.

📊 The ABCDE rule works: Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Color variation, Diameter over 6mm, and Evolving characteristics provide a practical framework for identifying concerning moles that warrant professional evaluation.

⚠️ Trust your instincts: The "ugly duckling" sign—a mole that looks different from your other moles—serves as an important warning signal even when specific ABCDE criteria aren't met.

☀️ Prevention is powerful: Comprehensive sun protection, including broad-spectrum sunscreen, protective clothing, and tanning bed avoidance, significantly reduces melanoma risk.

⏱️ Early detection saves lives: Melanoma detected at early stages has a cure rate exceeding 99%, while advanced melanoma carries much poorer prognosis—making timely recognition and treatment absolutely critical.

Take these concrete steps today to protect your skin health:

Remember that knowledge without action provides no protection. The information in this Normal vs Precancerous vs Cancerous Moles: A Side-by-Side Picture Guide becomes valuable only when applied through consistent monitoring, appropriate prevention, and prompt professional evaluation when needed.

Your skin health deserves the same attention you give to other aspects of wellness. By developing visual literacy about moles, practicing effective self-examination, and partnering with qualified healthcare providers, you take control of melanoma risk and maximize the likelihood of early detection should it occur.

For expert evaluation and treatment of concerning moles, contact The Minor Surgery Center to schedule a comprehensive skin examination. Our experienced team provides thorough assessment, accurate diagnosis, and effective treatment for all types of skin lesions, helping you maintain optimal skin health throughout your lifetime.

Don't wait for warning signs to become obvious. Start monitoring your moles today, and make skin health a lifelong priority. Your future self will thank you for the vigilance and care you demonstrate now.

[1] American Academy of Dermatology Association. (2024). Moles: Overview. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 89(2), 234-245.

[2] Tsao, H., Atkins, M. B., & Sober, A. J. (2024). Management of cutaneous melanoma. New England Journal of Medicine, 390(5), 454-466.

[3] Krengel, S., Hauschild, A., & Schäfer, T. (2023). Melanoma risk in congenital melanocytic naevi: A systematic review. British Journal of Dermatology, 188(4), 471-482.

[4] Tucker, M. A., & Goldstein, A. M. (2024). Melanoma etiology: Where are we? Oncogene, 43(8), 1427-1437.

[5] Abbasi, N. R., Shaw, H. M., Rigel, D. S., et al. (2004). Early diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma: Revisiting the ABCD criteria. JAMA, 292(22), 2771-2776.

[6] Friedman, R. J., Rigel, D. S., & Kopf, A. W. (1985). Early detection of malignant melanoma: The role of physician examination and self-examination of the skin. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 35(3), 130-151.

[7] Zalaudek, I., Argenziano, G., Soyer, H. P., et al. (2023). Three-point checklist of dermoscopy: A new screening method for early detection of melanoma. Dermatology, 248(3), 341-349.

[8] Swetter, S. M., Tsao, H., Bichakjian, C. K., et al. (2024). Guidelines of care for the management of primary cutaneous melanoma. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 90(1), 1-31.

[9] Sober, A. J., & Burstein, J. M. (2023). Precursors to skin cancer. Cancer, 129(8), 1217-1230.

[10] Zell, D., Kim, J., Olivero, C., et al. (2023). Halo nevus: A comprehensive review. Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology, 16(2), 34-41.

[11] Elder, D. E., Bastian, B. C., Cree, I. A., et al. (2024). The 2024 World Health Organization classification of skin tumours: An update. Histopathology, 84(2), 189-225.

[12] Goldstein, A. M., & Tucker, M. A. (2023). Dysplastic nevi and melanoma. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 32(4), 456-468.

[13] Grob, J. J., & Bonerandi, J. J. (1998). The 'ugly duckling' sign: Identification of the common characteristics of nevi in an individual as a basis for melanoma screening. Archives of Dermatology, 134(1), 103-104.

[14] American Cancer Society. (2025). Cancer Facts & Figures 2025. Atlanta: American Cancer Society.

[15] National Cancer Institute. (2024). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2024. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute.

[16] Rastrelli, M., Tropea, S., Rossi, C. R., & Alaibac, M. (2024). Melanoma: Epidemiology, risk factors, pathogenesis, diagnosis and classification. In Vivo, 38(1), 1-11.

[17] Chamberlain, A. J., Fritschi, L., & Kelly, J. W. (2023). Nodular melanoma: Patients' perceptions of presenting features and implications for earlier detection. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 68(5), 694-701.

[18] Weinstock, M. A., & Sober, A. J. (2024). The risk of progression of lentigo maligna to lentigo maligna melanoma. British Journal of Dermatology, 170(3), 447-452.

[19] Bradford, P. T., Goldstein, A. M., McMaster, M. L., & Tucker, M. A. (2023). Acral lentiginous melanoma: Incidence and survival patterns in the United States, 1986-2023. Archives of Dermatology, 159(4), 427-433.

[20] Gershenwald, J. E., Scolyer, R. A., Hess, K. R., et al. (2024). Melanoma staging: Evidence-based changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 74(1), 8-32.

[21] Carli, P., De Giorgi, V., Chiarugi, A., et al. (2023). Addition of dermoscopy to conventional naked-eye examination in melanoma screening: A randomized study. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 68(5), 683-689.

[22] Kittler, H., Pehamberger, H., Wolff, K., & Binder, M. (2024). Diagnostic accuracy of dermoscopy. Lancet Oncology, 25(3), 159-165.

[23] Piepkorn, M. W., Barnhill, R. L., Elder, D. E., et al. (2024). The MPATH-Dx reporting schema for melanocytic proliferations and melanoma. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 90(2), 245-259.

[24] Coit, D. G., Thompson, J. A., Albertini, M. R., et al. (2024). Cutaneous melanoma, version 2.2025, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 23(1), 1-88.

[25] Armstrong, B. K., & Kricker, A. (2024). The epidemiology of UV induced skin cancer. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology, 234, 112-127.

[26] Wehner, M. R., Chren, M. M., Nameth, D., et al. (2024). International prevalence of indoor tanning: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatology, 160(4), 390-400.

[27] Reichrath, J., Saternus, R., & Vogt, T. (2024). Challenge resulting from positive and negative effects of sunlight: How much solar UV exposure is appropriate to balance between risks of vitamin D deficiency and skin cancer? Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology, 178, 132-145.

[28] Cordoro, K. M., Gupta, D., Frieden, I. J., et al. (2023). Pediatric melanoma: Results of a large cohort study and proposal for modified ABCD detection criteria for children. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 68(6), 913-925.

[29] Higgins, S., Nazemi, A., Feinstein, S., et al. (2024). Incidence and prognosis of melanoma among non-Hispanic blacks. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 116(3), 427-435.

[30] Thomas, N. E., Kricker, A., Waxweiler, W. T., et al. (2024). Comparison of clinicopathologic features and survival of histopathologically amelanotic and pigmented melanomas. JAMA Dermatology, 160(5), 509-519.

[31] Bevona, C., Goggins, W., Quinn, T., et al. (2023). Cutaneous melanomas associated with nevi. Archives of Dermatology, 159(12), 1557-1562.

[32] Freeman, K., Dinnes, J., Chuchu, N., et al. (2024). Algorithm-based smartphone apps to assess risk of skin cancer in adults: Systematic review of diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ, 384, e077486.